Luigi Galvani (1737-1798)

A century and a half after Galileo's death, something of scientific importance

was to develop in Italy. During the 1780's, biologist Luigi Galvani performed

experimentsat the University of Bologna involving electric charges and frogs.

It had been found that a charge applied to the spinal cord of a frog could generate

muscular spasms throughout its body. Charges could make frog legs jump even

if the legs were no longer attached to a frog. While cutting a frog leg, Galvani's

steel scalpel touched a brass hook that was holding the leg in place. The leg

twitched. Further experiments confirmed this effect, and Galvani was convinced

that he was seeing the effects of what he called animal electricity, the life

force within the muscles of the frog. At the University of Pavia, Galvani's

colleague Alessandro Volta was able

to reproduce the results, but was sceptical of Galvani's explanation.

A century and a half after Galileo's death, something of scientific importance

was to develop in Italy. During the 1780's, biologist Luigi Galvani performed

experimentsat the University of Bologna involving electric charges and frogs.

It had been found that a charge applied to the spinal cord of a frog could generate

muscular spasms throughout its body. Charges could make frog legs jump even

if the legs were no longer attached to a frog. While cutting a frog leg, Galvani's

steel scalpel touched a brass hook that was holding the leg in place. The leg

twitched. Further experiments confirmed this effect, and Galvani was convinced

that he was seeing the effects of what he called animal electricity, the life

force within the muscles of the frog. At the University of Pavia, Galvani's

colleague Alessandro Volta was able

to reproduce the results, but was sceptical of Galvani's explanation.

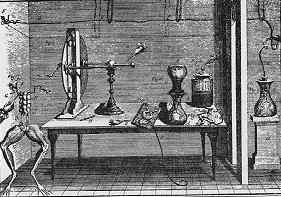

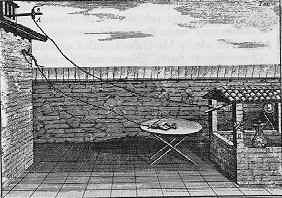

The Italian anatomist and physician Luigi Galvani was one of the first to investigate experimentally the phenomenon of what came to be named "bioelectrogenesis". In a series of experiments started around 1780, Galvani, working at the University of Bologna, found that the electric current delivered by a Leyden jar or a rotating static electricity generator would cause the contraction of the muscles in the leg of a frog and many other animals, either by applying the charge to the muscle or to the nerve.In the strange case of Galvani's frog, this twitching happened even when its legs were not in a direct circuit with the machine. Galvani had placed the lower section of a dissected frog on a table near a plate-type electrical machine.

Then two things occurred simultaneously causing Galvani to stop and wonder. An assistant was drawing a spark from the brass conductor of the electrical machine when a knife held in his hand touched the crural or sciatic nerve passing through the lower part of the spine into the frog's legs. There was an immediate twitch of the muscles and a kick of the legs as if a severe cramp had set in. Galvani wrote, "While one of those who were assisting me touched lightly, and by chance, the point of his scalpel to the internal crural nerves of the frog, suddenly all the muscles of its limbs were seen to be so contracted that they seemed to have fallen into tonic convulsions.

Giovanni Aldini, Galvani's nephew, was the greatest of all Galvani’s supporters. He helped to organize a society at Bologna to foster the practices of galvanism in opposition to a Volta society established at the University of Pavia. Aldini traveled all over Europe publicly electrifying human and animal bodies, and his performances were extraordinary theatrical spectacles. "Galvani knew that metals transmitted this mysterious substance called electricity, and came to the obvious conclusion that some kind of electricity - which he called "animal electricity" - was generated in the tissue of the frog and, flowing through the metal skewer and fence, activated the frog's muscles. He distinguished this kind of electricity from "artificial electricity" generated by friction (static electricity) and from "natural electricity" such as lightning. He thought of "animal electricity" as a fluid secreted by the brain, and proposed that flow of this fluid through the nerves activated the muscles.

Galvani and corrosion monitoring

Galvani and galvanic corrosion

Galvani's remarkable experiments helped to establish the basis for the biological study of neurophysiology and neurology. The paradigm shift was complete: nerves were not water pipes or channels, as Descartes and his contemporaries thought, but electrical conductors. Information within the nervous system was carried by electricity generated directly by the organic tissue. As the result of the experimental demonstrations carried out by Luigi Galvani and his followers, the electrical nature of the nerve-muscle function was unveiled. However, a direct proof could only be made when scientists could be able to measure or to detect the natural electrical currents generated in the nervous and muscular cells. Galvani did not have the technology to measure these currents, because they were too small.

Luigi Galvani was appointed Reader in Anatomy at the University in 1762. His skill as a surgeon soon won him the Chair of Obstetrics at the Institute of Sciences, of which he was to become president in 1772. His investigations into the structure of animal organs established him as one of the founders of modern electro-technology at the end of the eighteenth century, alongside his contemporaries Henry Cavendish, Benjamin Franklin and Alessandro Volta. He was the first to discover the physiological action of electricity. His subsequent experiments in making the exposed muscles and nerves of a frog contract when connected to a demonstrated the existence of bioelectric forces in animal tissue.

This gave rise to a disagreement between Galvani and Volta over the explanation of the phenomenon, about which each was partly right. His work was nevertheless instrumental in leading Volta to the invention of the first electric battery without which, some of today's electronics may not have existed . Galvani held his Chair for 33 years but was dismissed in 1797 following the occupation of the country by the Napoleonic army. Being a man of integrity, he refused to take the oath of allegiance required of him by the invader. He died the following year.

The name Galvanization is derived from Luigi Galvani, and was once used as the name for the administration of electric shocks (also termed in the 19th century Faradism, named after Michael Faraday), this stems from Galvani's induction of twitches in severed frog's legs, by his accidental generation of electricity. This now archaic sense is the origin of the meaning of galvanized when used to describe someone stirred to sudden, abrupt action.

Connect with us

Contact us today